RJ GAUDET & ASSOCIATES L.L.C.

"Let us realize the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice."

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Archive for September, 2015

Will Class Actions Get the Hammer Next Term? The high court will take up cases further defining the rights of consumers suing corporations.

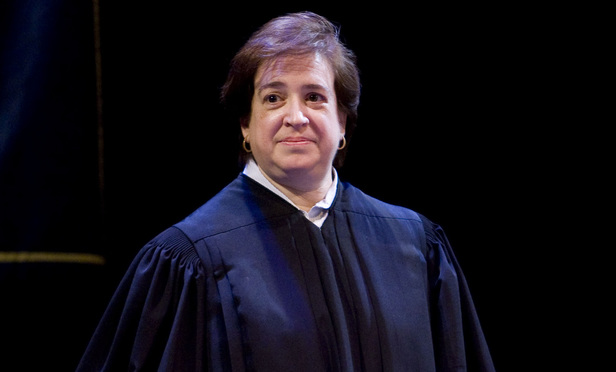

By Arthur H. Bryant*

Two years ago, dissenting in American Express v. Italian Colors Restaurant, Justice Elena Kagan, referring to the civil procedure rule on class actions, wrote, “To a hammer, everything looks like a nail. And to a court bent on diminishing the usefulness of Rule 23, everything looks like a class action, ready to be dismantled.” The message to people and companies involved in class actions was clear: “Be afraid. Be very afraid.”

Last term, the U.S. Supreme Court basically left class actions alone. This upcoming term, however, the court has already agreed to hear four cases that could dramatically restrict or terminate class action litigation in numerous ways. The concern is real. Will the court keep hammering class actions or let them be?

To understand why so many are worried, just look at the decisions that prompted Kagan’s remarks. In 2011, AT&T Mobility v. Concepcion effectively held that the Federal Arbitration Act gave corporations the power to violate state laws and use mandatory arbitration clauses in their form contracts to bar customers and workers from bringing class actions against them.

Wal-Mart Stores v. Dukes announced several new rules making it harder to prosecute cases as class actions and precluded the courts from determining whether the country’s largest private employer was discriminating against its female workers nationwide.

In 2013, neither Comcast v. Behrend, an antitrust case, nor Genesis Healthcare v. Symczyk, a Fair Labor Standards Act case, presented the questions the court heard them to address. But, instead of dismissing them, the court stopped both from proceeding as class actions on grounds not addressed by the parties.

Finally, in American Express, the court held corporations could use mandatory arbitration clauses to ban class actions when, as a practical matter, that prevented their customers from vindicating their substantive rights and let the companies illegally obtain billions.

FOUR NEW CHALLENGES

Against this background, the court’s decision to hear four new challenges to class actions has understandably raised grave concerns. Tyson Foods v. Bouaphakeo, attacking a $5.8 million jury verdict against the company for underpaying its workers, raises two questions: first, whether the trial judge should have permitted Tyson’s workers to rely on statistical sampling to establish liability and damages; and second, whether a class can be certified that contains some members who have not been injured and have no legal right to damages.

But statistical sampling has been used to establish liability and damages in cases for years. And classes have always been certified even though they contain some members who have not been injured and are not entitled to damages. For example, even if an employer is discriminating against women in hiring, unqualified female job applicants would not have been injured or be entitled to damages. That fact has never stopped class actions charging gender discrimination in hiring from proceeding.

In Spokeo v. Robins, a Fair Credit Reporting Act case, the company, charged with publishing inaccurate information and failing to provide legally required notices, contends that Congress cannot constitutionally give people the right to seek statutory damages, individually or collectively, when corporations violate the law.

Based on this rationale, it urges the court to bar class actions for statutory damages authorized by Congress to enforce the Truth in Lending Act, Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, Telephone Consumer Protection Act, Employee Retirement Income Security Act, Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act, Lanham Act, Fair Housing Act, Americans With Disabilities Act, Video Privacy Protection Act, Electronic Communications Privacy Act, Stored Communications Act, Cable Communications Privacy Act, Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act, Expedited Funds Availability Act, Homeowners Protection Act, Equal Credit Opportunity Act and the Driver’s Privacy Protection Act.

Campbell-Ewald v. Gomez presents the question the court granted review of Genesis Healthcare to decide: whether defendants can stop class actions and render them moot by offering the individual class representatives their full damages and the class members nothing. Since Genesis Healthcare, the lower courts have unanimously agreed that Kagan’s dissent in that case was right: the answer is no. But the court took the case anyway.

And, in DirecTV v. Imburgia, which charges early-cancellation penalties imposed on consumers were illegal, the company’s 2007 customer agreement said its mandatory arbitration clause was invalid if the clause’s class action ban violated “the law of your state.” It did. AT&T Mobility later held federal law pre-empted that state law, but the lower court found that didn’t matter — because the parties’ agreement was to follow state law. Contract interpretation is supposed to be governed by state law, which the Supreme Court does not create. The court could, however, still find a way to enforce the class action ban.

These cases are important to everyone in America. While they involve class actions — a procedural device — what’s at stake are the substantive and constitutional rights class actions are designed to preserve and enforce. When corporations or the government harm many people or businesses, class actions are often the only way that justice can be done.

The court will be deciding whether class actions can continue to be used, as they have been, to enforce state and federal consumer protection, employment, civil rights, civil liberties, environmental and other laws — and the state and U.S. constitutions. If it keeps hammering nails in class actions’ coffin, it could be burying significant portions of these laws as well. We will see.

*Arthur H. Bryant is the chairman of Public Justice, a national public interest law firm dedicated to advancing and preserving access to justice for all. His practice focuses on consumers’ rights, workers’ rights, civil rights, environmental protection, and corporate and government accountability.

[Reprinted from the National Law Journal (Sept. 7, 2015) with permission of Arthur Bryant, chairman of Public Justice. Mr. Gaudet is a member of Public Justice.]

By Arthur Bryant

Chairman, Public Justice

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s Institute for Legal Reform just released the latest version of the propaganda piece it started publishing in 2002. Entitled “2015 Lawsuit Climate Survey: Ranking the States,” the report summarizes the answers of a “nationally representative sample of 1,203 in-house general counsel, senior litigators or attorneys, and other senior executives who are knowledgeable about litigation matters at companies with annual revenues over $100 million” who responded to what it calls a “survey.” The so-called “survey” does not, however, show what these people really think. Everyone taking it knows that its purpose is – as it has been for the past 13 years – to give big business a basis to smear state court systems that aren’t pro-business enough as “judicial hellholes” and push all state courts to limit corporate liability for wrongdoing.

Even so, the answers provide some extraordinary information.

First, Corporate America’s representatives say that state courts are increasingly better for them. Consumer, worker, environmental, and civil rights advocates would agree. As the report says, in the 13 years since the so-called survey began, “there has been a general increase in the overall average score” given to state court systems by lawyers for big business – “and this trend continues with the 2015 survey.”

“From 2002-2006,” the report finds, “the overall score averaged approximately 52.9, whereas from 2007-2015, the score averaged approximately 59.6.” Chart 2 of the report gives the details and shows that the score given by big businesses’ lawyers to state court systems has gone up almost every year. In 2003, Corporate America’s lawyers gave the state courts a score of 50.7; in 2015, they gave them a score of 61.7.

Since this is supposed to be the views of one side in an adversarial system, wouldn’t a score close to 50 be ideal? The Chamber’s propaganda campaign (backed by corporate lobbying, campaign donations, and decisions like Citizens United) is plainly working. I understand that, in theory, a system perceived to be fair by all parties should get a score of 100 from everyone but, remember, this was a “survey” taken by specific people of specific people for a specific purpose: to push the state courts in the corporations’ favor. You could reasonably expect a court system that got a score of 100 from these participants to get a score of zero from lawyers trying to hold big businesses accountable for breaking the law.

Second, even in a “survey” designed and taken to show that the state courts are biased against big business, half of Corporate America’s lawyers say the state court liability systems overall are “excellent or pretty good.” Another 41% say the systems overall are “only fair.” I thought the goal was for them to all be “fair.” But perhaps that’s why I’m a public interest lawyer, not a lawyer for big business. Despite the reason for the “survey,” only 8% said the systems overall were “poor” (the last 1% was not sure or declined to answer).

In other words, despite what the “survey” is intended to show, it actually shows that the state court systems overall are viewed by Corporate America’s lawyers as significantly better for big businesses than they are for the people and companies suing them. Can you imagine the cries of bias we would hear if a survey showed legal services, consumer, and workers’ lawyers saying the courts were “excellent or pretty good” for them (much less “only fair”) in lawsuits against big business?

Third, Corporate America’s lawyers give grades between A and F to each of the state court systems and say where they do and don’t like to be sued. In a stunning and continuing display of arrogance, they actually include a map of the “Best to Worst Legal systems in America.” The map was apparently created in Bizarro World. They give As to 14% of the state courts, Bs to 38%, Cs to 27%, and Ds to 11%. In other words, even according to these “survey” respondents, 90% of the state court systems are passing. They give failing grades, Fs, to 5%. The other 5% were not sure or declined to answer. These answers, too, put the lie to Corporate America’s claims that state courts need to be more favorable to them. If anything, they show that many state courts are already far more favorable to big businesses than they are to those trying to hold big businesses accountable.

The “survey” respondents also took the time to tell us which states’ courts are the most, and least, favorable to Corporate America. The top five states, according to them, are Delaware (often called a subsidiary of DuPont), Vermont, Nebraska, Iowa, and New Hampshire. See any states in there with a lot of minorities and poor people who might not look kindly on big corporations abusing their power? The bottom five states, they say, are West Virginia, Louisiana, Illinois, California, and New Mexico. Ask yourself the same question. I question some of these rankings. Most plaintiffs’ lawyers would list the Texas state courts as one of the most pro-business in the nation. But maybe the state’s so big that they don’t want to admit that. The states they rank highest are all fairly small.

If you want to figure out which states have juries most likely to hold big corporations accountable, try reversing the order. These are the states the Chamber of Commerce regularly uses this “survey” to label “judicial hellholes.” In reality, however, a “hellhole” for corporations violating the law may be “heaven” for those seeking justice against businesses that cheat or injure consumers (for more on this, click here).

What we need in America are state and federal court systems that are fair – and biased in no one’s favor. Unfortunately, the Chamber of Commerce’s latest propaganda piece shows we are far from that goal and, for some time, things have been getting worse. Big businesses’ own lawyers say that state court systems have turned increasingly in Corporate America’s favor since the “survey” began.

This needs to stop. Our courts systems need to turn back to being even-handed. That’s the only way justice can be done.

[Reprinted with permission of Mr. Bryant. Mr. Gaudet is a member of Public Justice, the organized chaired by Mr. Bryant.]

Second Circuit: Class of Argentine Bondholders Cannot Include Owners of Beneficial Interests At Any Time, Too Broad

By Robert J. Gaudet, Jr.

Today, in a decision that is sure to delight the Argentine critics of Judge Griesa (and Argentina’s lawyers, one of whom has already said he is “very pleased”), a panel of three judges of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reversed an August 29, 2014 order by Judge Griesa to expand the class definition of bondholders in Brecher v. Argentina, one of numerous class actions against Argentina.

On August 29, 2014, Judge Griesa had expanded the class, at the plaintiffs’ request, to include “all holders of Republic of Argentina European Medium Term Note Bond, with a coupon rate of 9.25% and a maturity date of July 20, 2004 (ISIN XS011 3833510)” without limitation as to time held. The Second Circuit held that this definition was too broad and violated the requirement that the class be “ascertainable.”

Today, the Second Circuit gave a puzzling hypothetical that, in its opinion, demonstrated that the new class definition was not ascertainable:

A hypothetical illustrates this problem. Two bondholders—A and B—each

hold beneficial interests in $50,000 of bonds. A opts out of the class, while B opts

in. Both A and B then sell their interests on the secondary market to a third

party, C. C now holds a beneficial interest in $100,000 of bonds, half inside the

class and half outside the class. If C then sells a beneficial interest in $25,000 of

bonds to a fourth party, D, neither the purchaser nor the court can ascertain

whether D’s beneficial interest falls inside or outside of the class.3 Even if there

were a method by which the beneficial interests could be traced, determining

class membership would require the kind of individualized mini‐hearings that

run contrary to the principle of ascertainability. See Charron, 269 F.R.D. at 229;

Bakalar, 237 F.R.D. at 64–66. The features of the bonds in this case thus make the

modified class insufficiently definite as a matter of law. Although the class as

originally defined by the District Court may have presented difficult questions of

calculating damages, it did not suffer from a lack of ascertainability. The District

Court erred in attempting to address those questions by introducing an

ascertainability defect into the class definition.

This hypothetical makes little sense. For instance, it assumes that it is possible that “A opts out of the class, while B opts in.” However, this is not even possible in a Rule 23(b)(3) class action, as Brecher v. Argentina was certified under Rule 23(b)(3). In such a case, bondholders are automatically members of an opt-out class unless they exclude themselves by opting out. There is no requirement or procedure by which any party “opts in.” The opt in procedure is a part of opt-in class actions brought under the Fair Labor Standards Act (and it is also a primary feature of class actions in many European countries, like Sweden and Italy, where the mechanism is rarely used) but it is not a part of a Rule 23(b)(3) class action. The Court’s hypothetical suggests a fundamental misunderstanding of the way a Rule 23(b)(3) class action functions even though the panel’s opinion may be correct in other respects.

The problem identified by the Second Circuit could be cured. For instance, the class definition could be adjusted to include owners of beneficial interests at a certain point in time, e.g., at the time of final judgment or settlement. Even this would be an improvement over the initial class definition that required bondholders to continuously hold their bonds from the date of class certification until the date of final judgment in order to be a part of the class. It appears the Second Circuit may wish for the parties to return to this original class definition although it is not entirely clear.

The Second Circuit’s decision is further puzzling because it seems to add a new requirement, on remand, that does not seem to have any direct relationship to the class definition, the issue that was on appeal. Specifically, the Second Circuit seems to say in today’s opinion that the parties must know make a reasonable estimate of class damages and, if they are unable to do so, then they must estimate damages for individual members of the class:

There remains the question of determining damages on remand. Given

that Appellee here is identically situated to the Seijas plaintiffs and this Court has

already addressed the requirements for determining damages in those cases, we

conclude that the District Court should apply the same process dictated by Seijas

II for calculating the appropriate damages:

Specifically, it shall: (1) consider evidence with respect

to the volume of bonds purchased in the secondary

market after the start of the class periods that were not

tendered in the debt exchange offers or are currently

held by opt‐out parties or litigants in other proceedings;

(2) make findings as to a reasonably accurate, nonspeculative

estimate of that volume based on the

evidence provided by the parties; (3) account for such

volume in any subsequent damage calculation such that

an aggregate damage award would “roughly reflect”

the loss to each class, see Seijas I, 606 F.3d at 58–59; and

(4) if no reasonably accurate, non‐speculative estimate

can be made, then determine how to proceed with

awarding damages on an individual basis. Ultimately,

if an aggregate approach cannot produce a reasonable

approximation of the actual loss, the district court must

adopt an individualized approach.

493 F. App’x at 160; see also Seijas III, 2015 WL 4716474, at *4 (repeating

instructions). The hearing will ensure that damages do not “enlarge[] plaintiffs’

rights by allowing them to encumber property to which they have no colorable

claim.” Seijas I, 606 F.3d at 59.

This latter part of the 10-page opinion is also puzzling because there is no apparent reason why an estimate of damages would be necessary at this stage of the proceedings. There is no settlement to discuss. There is no motion for judgment or any order of judgment on the docket. Hence, it is not necessary to estimate damages in Brecher at this moment, so it appears the Second Circuit panel decided issues that were not before it and that it may not be necessary for Judge Griesa to hold a hearing over at this stage.

The Second Circuit’s panel decision is available at this link: 2d Circuit – Sept 16 2015. It is unclear whether the plaintiffs will file a petition for rehearing by a full panel of the Second Circuit but that may be advisable since the panel opinion seems to misunderstand the functioning, e.g., of a Rule 23 opt-out class action.

Mr. Gaudet of RJ Gaudet & Associates LLC drafted the original complaint in Brecher v. Argentina when he was a lawyer at a previous law firm. He has not worked on the case since he resigned from that firm in 2007 and the expanded class definition that was reversed by the Second Circuit was not related to his work.

Lawyers Mr. Gaudet, Jenik Radon, and Tim Ashby currently serve as class counsel in a separate class action against Argentina, Barboni v. Argentina, in which they are assisted by English barrister, Dr. Ingrid Detter de Frankopan, of the United Kingdom, who is an expert in the field of international law.