RJ GAUDET & ASSOCIATES L.L.C.

"Let us realize the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice."

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Will Class Actions Get the Hammer Next Term? The high court will take up cases further defining the rights of consumers suing corporations.

By Arthur H. Bryant*

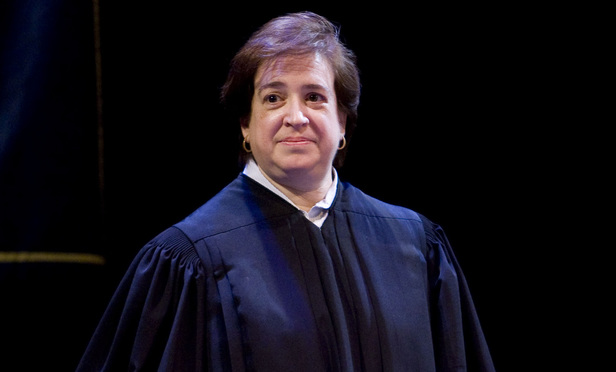

Two years ago, dissenting in American Express v. Italian Colors Restaurant, Justice Elena Kagan, referring to the civil procedure rule on class actions, wrote, “To a hammer, everything looks like a nail. And to a court bent on diminishing the usefulness of Rule 23, everything looks like a class action, ready to be dismantled.” The message to people and companies involved in class actions was clear: “Be afraid. Be very afraid.”

Last term, the U.S. Supreme Court basically left class actions alone. This upcoming term, however, the court has already agreed to hear four cases that could dramatically restrict or terminate class action litigation in numerous ways. The concern is real. Will the court keep hammering class actions or let them be?

To understand why so many are worried, just look at the decisions that prompted Kagan’s remarks. In 2011, AT&T Mobility v. Concepcion effectively held that the Federal Arbitration Act gave corporations the power to violate state laws and use mandatory arbitration clauses in their form contracts to bar customers and workers from bringing class actions against them.

Wal-Mart Stores v. Dukes announced several new rules making it harder to prosecute cases as class actions and precluded the courts from determining whether the country’s largest private employer was discriminating against its female workers nationwide.

In 2013, neither Comcast v. Behrend, an antitrust case, nor Genesis Healthcare v. Symczyk, a Fair Labor Standards Act case, presented the questions the court heard them to address. But, instead of dismissing them, the court stopped both from proceeding as class actions on grounds not addressed by the parties.

Finally, in American Express, the court held corporations could use mandatory arbitration clauses to ban class actions when, as a practical matter, that prevented their customers from vindicating their substantive rights and let the companies illegally obtain billions.

FOUR NEW CHALLENGES

Against this background, the court’s decision to hear four new challenges to class actions has understandably raised grave concerns. Tyson Foods v. Bouaphakeo, attacking a $5.8 million jury verdict against the company for underpaying its workers, raises two questions: first, whether the trial judge should have permitted Tyson’s workers to rely on statistical sampling to establish liability and damages; and second, whether a class can be certified that contains some members who have not been injured and have no legal right to damages.

But statistical sampling has been used to establish liability and damages in cases for years. And classes have always been certified even though they contain some members who have not been injured and are not entitled to damages. For example, even if an employer is discriminating against women in hiring, unqualified female job applicants would not have been injured or be entitled to damages. That fact has never stopped class actions charging gender discrimination in hiring from proceeding.

In Spokeo v. Robins, a Fair Credit Reporting Act case, the company, charged with publishing inaccurate information and failing to provide legally required notices, contends that Congress cannot constitutionally give people the right to seek statutory damages, individually or collectively, when corporations violate the law.

Based on this rationale, it urges the court to bar class actions for statutory damages authorized by Congress to enforce the Truth in Lending Act, Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, Telephone Consumer Protection Act, Employee Retirement Income Security Act, Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act, Lanham Act, Fair Housing Act, Americans With Disabilities Act, Video Privacy Protection Act, Electronic Communications Privacy Act, Stored Communications Act, Cable Communications Privacy Act, Migrant and Seasonal Agricultural Worker Protection Act, Expedited Funds Availability Act, Homeowners Protection Act, Equal Credit Opportunity Act and the Driver’s Privacy Protection Act.

Campbell-Ewald v. Gomez presents the question the court granted review of Genesis Healthcare to decide: whether defendants can stop class actions and render them moot by offering the individual class representatives their full damages and the class members nothing. Since Genesis Healthcare, the lower courts have unanimously agreed that Kagan’s dissent in that case was right: the answer is no. But the court took the case anyway.

And, in DirecTV v. Imburgia, which charges early-cancellation penalties imposed on consumers were illegal, the company’s 2007 customer agreement said its mandatory arbitration clause was invalid if the clause’s class action ban violated “the law of your state.” It did. AT&T Mobility later held federal law pre-empted that state law, but the lower court found that didn’t matter — because the parties’ agreement was to follow state law. Contract interpretation is supposed to be governed by state law, which the Supreme Court does not create. The court could, however, still find a way to enforce the class action ban.

These cases are important to everyone in America. While they involve class actions — a procedural device — what’s at stake are the substantive and constitutional rights class actions are designed to preserve and enforce. When corporations or the government harm many people or businesses, class actions are often the only way that justice can be done.

The court will be deciding whether class actions can continue to be used, as they have been, to enforce state and federal consumer protection, employment, civil rights, civil liberties, environmental and other laws — and the state and U.S. constitutions. If it keeps hammering nails in class actions’ coffin, it could be burying significant portions of these laws as well. We will see.

*Arthur H. Bryant is the chairman of Public Justice, a national public interest law firm dedicated to advancing and preserving access to justice for all. His practice focuses on consumers’ rights, workers’ rights, civil rights, environmental protection, and corporate and government accountability.

[Reprinted from the National Law Journal (Sept. 7, 2015) with permission of Arthur Bryant, chairman of Public Justice. Mr. Gaudet is a member of Public Justice.]