RJ GAUDET & ASSOCIATES L.L.C.

"Let us realize the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice."

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Vaccine Compensation Fund Plays Invaluable Role in Compensating Victims Whom Lawyers Would Not Otherwise Represent

By Robert J. Gaudet, Jr.

After reviewing a provocative article posted in the “Stanford Lawyer” by Stanford professor Nora Freeman Engstrom (a former classmate of mine) about the infirmities of the $3.4 billion no-fault Vaccine Injury Compensation Fund that was set up to compensate victims so they don’t have to go to court with a lawsuit, I shared the article with a Seattle plaintiff’s lawyer, Lee Burdette, who has filed numerous cases with the Vaccine compensation fund. His experience is “quite different than the picture she paints,” he wrote.

Nora’s article concludes the Vaccine compensation fund takes too long (up to 5 years) to resolve cases instead of resolving them within the 240-day deadline and that it does not provide the guaranteed equal treatment to each claimant. Therefore, generalizing from this basis, she suggests that alternative compensation mechanisms might be less useful than traditional litigation in compensating victims in other fields, e.g., medical malpractice.

In Lee’s experience, however, the Vaccine compensation fund provides adequate compensation for victims who otherwise would not find lawyers to represent them in lawsuits in court. In addition, many claims are processed quickly, Lee says, and it is only a subset of contested off-the-Table claims and fee disputes that take longer. Lee responded to my email as follows: “if someone did a case by case analysis I think they would find” the following, as written in his own words (with very minimal editing by me):

“1. Many petitions are filed that are a) completely bogus; b) unsupported by proper documentation (medical records, expert reports, etc.); c) pro se. These cases take a long time to get through the system because there is no more lenient court in the world than the vaccine court about giving claimants more time to get it right – if I need another 30, 60 or even 90 days to do something, I simply call my opposing counsel, they agree and we file a stipulation.

2. Much of the time between case opening and closing is often devoted to fee and cost disputes. You would be shocked at the fee applications some of the major firms submit. It appears that the game for them is to ask for as much as they can and then litigate or negotiate. (By the way, we have never had a fee request challenged – they have all been entered by stipulation).

3. The cases that are brought as Table Injuries go quite quickly. The Vaccine compensation program was designed around the idea that the injuries that are scientifically accepted as being caused by vaccines should be compensated without much discussion. That principle is followed in my view. However, some claimants seek special damages because of the cap of $250K on general damages. That, of course, leads to the typical push back from defendants. Nevertheless, the awards seem pretty generous to me (with the exception of the general damages cap, which is a disgrace – Congress’ fault, not the program).

4. Cases that are not Table Injuries take much longer – and that is understandable. Claimants are always pushing to get compensation for everything that happens to them following a vaccination. Some of these claims may be spurious; others may be unsupportable by science. (I wonder how the hundreds or thousands of autism cases affected Nora’s averages). In my view, the Special Masters cultivate the principle of giving any tie to the claimant. It is a loose “preponderance of the evidence” standard.

Now, most of our cases are non-Table Injuries. Our experience is that the vast majority of them don’t exceed the 240-day guideline. We do have a beef with how long it takes to get the claimant’s money and our money (separate checks) after the case is concluded. It can be, often is, a few to several months.

All in all, I think the program is superior to litigating against drug companies, which I’ve done many time. Most of the people who go through the Vaccine Court would not even be able to get an attorney if the only recourse was to sue Merck or its ilk. Just too expensive for the types of claims that are typical.”

Nora’s article says she “studied nearly three decades of previously untapped material” but it’s not clear whether she interviewed any plaintiff’s lawyers, like Lee, or gathered anecdotal information. The latter approach served Prof. Deborah Hensler very well when she wrote a well-regarded book on class actions when she was employed at the Rand Institute. Given the differences between Nora’s apparently paper-based research and Lee’s real-world experience, it may be that this topic deserves a more in-depth look with a different methodology. It was good of Nora to dig through decades of materials, shine the light of inquiry, and raise this topic for discussion. She has nicely served the public and academia with her research.

The fund is a subject of criticism and debate. According to an episode on NPR, as overheard by Lee, the government intentionally does not publicize the fund because it is concerned that people might become more scared about using vaccines.

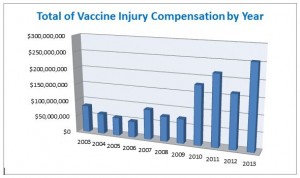

This chart shows the amount of money paid out to claimants each year by the Vaccine Injury Compensation Fund. Deciding these claims in one court in Washington, D.C. saves courts nationwide from having to process lawsuits around the country for damages.